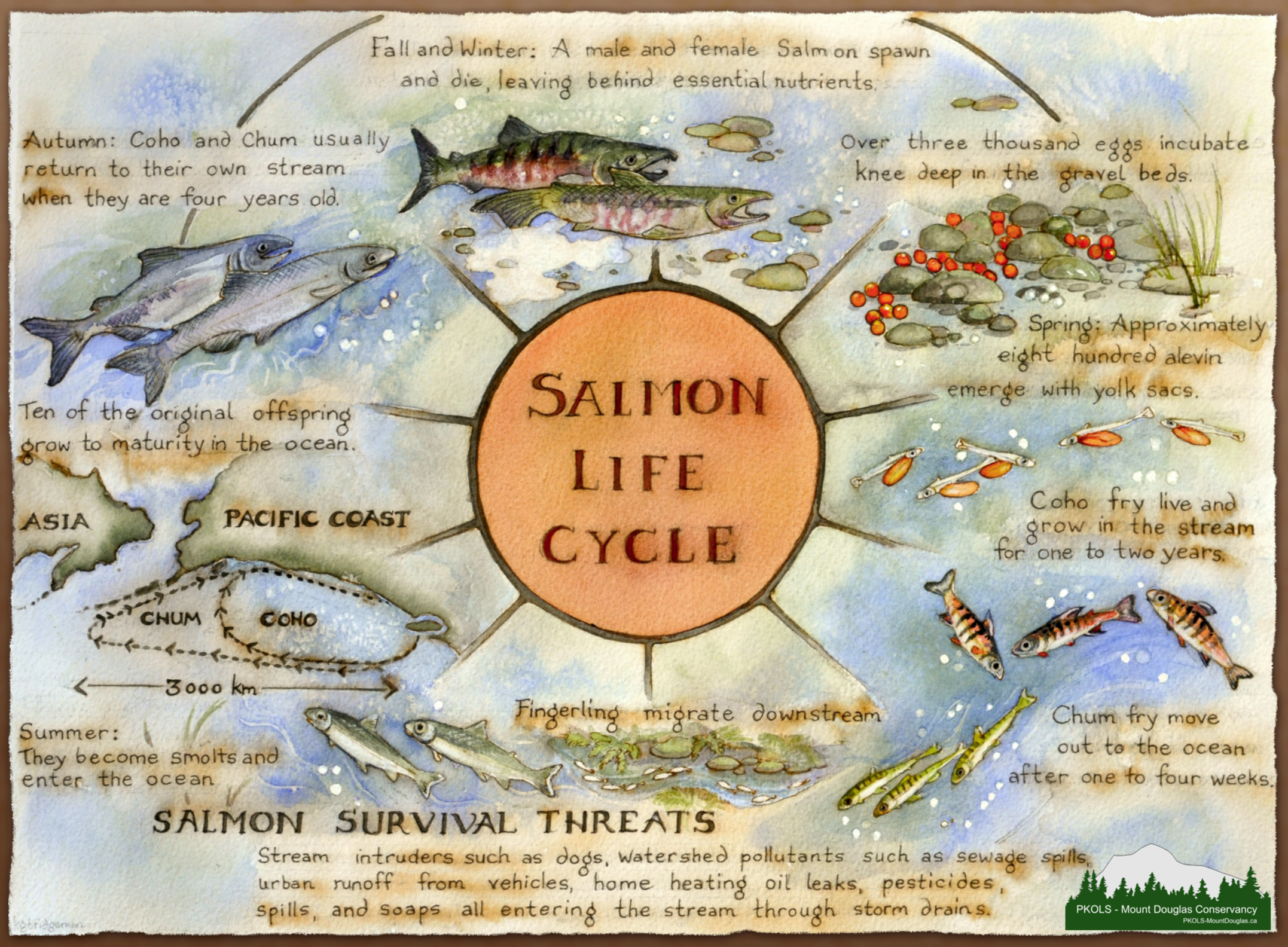

The salmon in Douglas Creek are predominantly chum, with some Coho although their numbers have substantially declined everywhere, with human assistance their presence is making a comeback. Salmon must jump many hurdles to survive intended, and human impact has added to these hurdles making their survival even harder. Chum are the 2nd largest species of pacific salmon, chinook being the largest, but chum are the poorest jumpers. Obstacles like waterfalls don’t stop other species of salmon but make it difficult for the chum. Often, this can stop their upstream migration resulting in them spawning further downstream. This is in part why you won’t find chum further upstream than Ash Road. Coho can easily make the migration further upstream.

An overview of the history, features, and fun facts about P’KOLS/Douglas Creek in Lekwungen & WSANEC territories/Victoria BC. Created by Corina Fischer, 2020.

When baby chum, called fry, leave their gravel nest they spend very little time in freshwater before heading out to sea, sometimes only a few weeks. Their migration to the ocean is second fastest only to pink salmon. Coho may spend a year or more in freshwater. Before all salmon leave fresh water, they must go through a physical change called smoltification to help them transition to saltwater. Very few fish can go from freshwater to saltwater and back again to

freshwater. Their bodies become more silvery and reflective, which acts as camouflage to protect them against predators in open water. There are also hormonal changes which impact the way they breathe and tolerate saltwater.

When salmon are in freshwater, their bodies need added salt, which they get through food. On the other hand, saltwater pulls water out of the salmon’s body through its skin. Because of this, they must drink salt water to replace lost water. Any excess salt in the salmon’s body is excreted through its gills and urine. At this lifecycle, stage salmon are called smolts. During this time, they are imprinting on their natal stream, taking in the smells and tastes so that they can navigate their way back in a few years.

After 3-5 years, adults come back to the creek they imprinted on at birth to spawn and die. Chum are generally the last of the salmon to return to their natal stream in the fall. Upon their return to freshwater, they go through another physical change and develop colourful bars on their body, green and purple, and the males grow large canines, and a hook jaw called a kype.

The females create a gravel nest called a redd by making a depression with her tail, where she will lay her eggs, as the male fertilizes them. Salmon will repeat this several times, continuously moving upstream until all the female’s eggs have been laid. The gravel that will cover the eggs, which is washed over them from the upstream redds being dug, protects them from predators and being washed away in heavy stream flow. Out of thousands of eggs each female will lay, only about 1% are likely to survive.

Salmon spawn in gravel that is pea to peach size so that it is small enough for the salmon to move but large enough to allow gaps for airflow. They prefer shallow sections where the water moves more quickly as the increased water flow keeps the redd oxygenated. Some of the current challenges salmon faces relate to their spawning preferences. Chum prefers streams close to the ocean, which tends to be more impacted by watershed corruption.

Human impact – how we can help

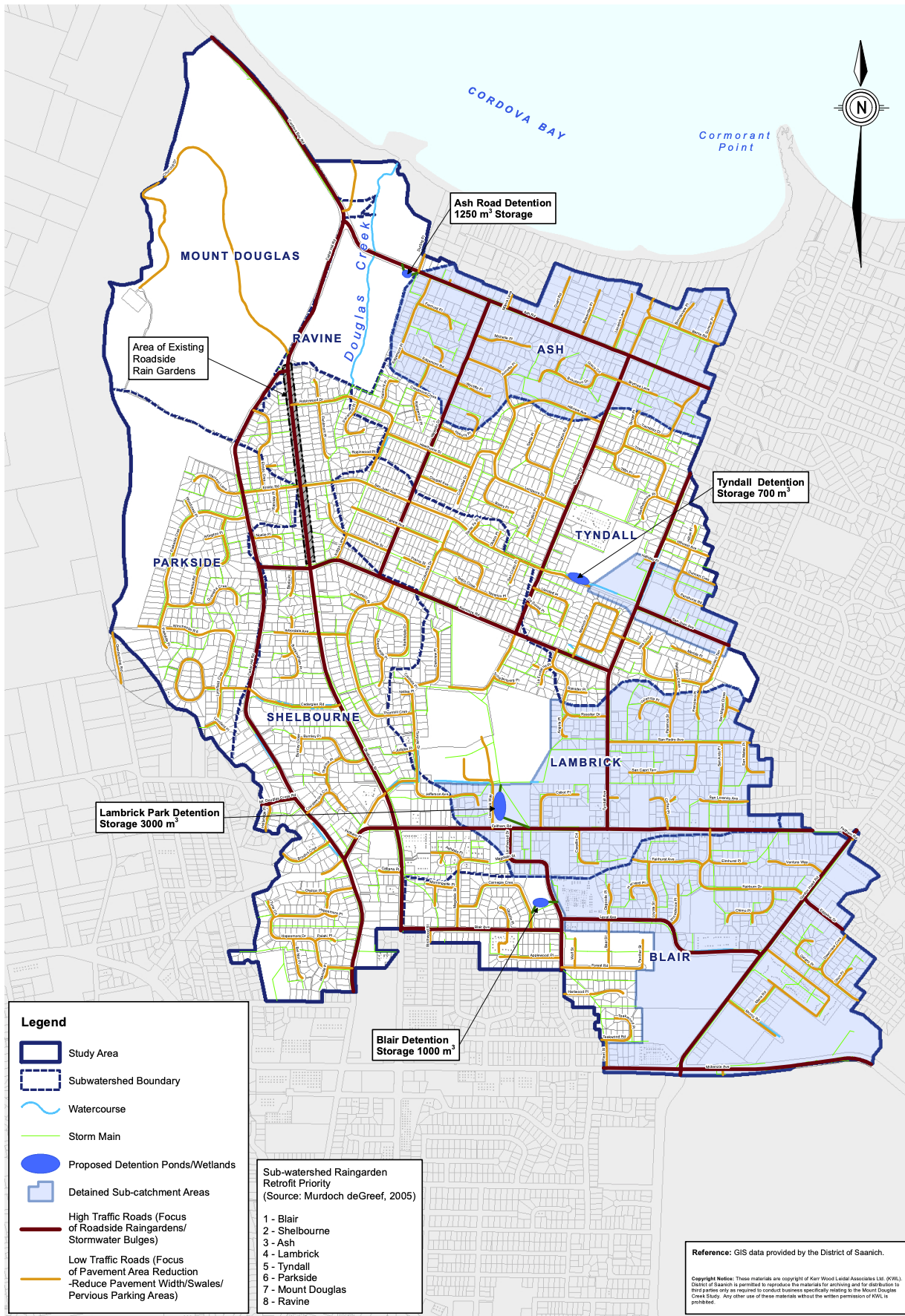

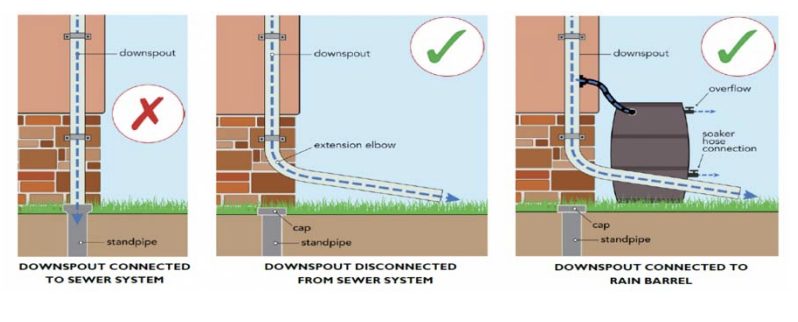

Due to an increase in non-porous surfaces in our city, when there is a storm, the water is unable to seep back into the ground and be filtered by the earth. It all goes into the storm drain and causes a surge of water which washes out the spawning beds, leaving nothing but clay. Because the storm drains are connected to Douglas Creek, there is also the challenge of coping with contaminants.

Spending time in nature provides peace and tranquillity to people’s otherwise chaotic lives. Parks everywhere are seeing an increase in human traffic, and along with them their four legged friends. The goal is to try and find a balance between humans and nature. Many aren’t aware that Mount Douglas Park is not a dog park, especially off leash. Although your dog may love running through the trees and rustling around in the ferns, this has a very negative impact on the ecosystem. New plant life, some endangered, get trampled; nesting animals like birds are scared off and potentially killed, and trails created by dogs pack the ground preventing things from growing in the future. If your dog needs some exercise, please take them to an appropriate place that is designed for them to run free without causing damage.

Dog droppings are another problem. Droppings that are left will eventually wash into the waterways increasing bacteria and degrading the water quality. This is not only harmful to the fish and plants but to humans as well. Please pick up your dog droppings, and don’t leave the bag on the trail or throw it in the bush. There are volunteers who work tirelessly to remove invasive species, helping to restore the ecosystem, and we don’t want them to have to encounter tossed feces.

Another issue parks are facing is people going off marked trails. It’s tempting to sneak down through the trees to get up close and personal with the creek, but please don’t. There are trails specifically chosen for human use so that nature and people can coincide. Rooted plants help keep the creek bank from eroding. It may not seem like a big deal but if these plants are trampled and die, and the ground is packed so nothing can grow, it will result in the creek banks eroding and ultimately the death of that area. Not to mention the risk of stepping on a redd upon entering the creek and crushing the eggs. Countless hours are being put into restoring the plant life that has been trampled by humans and their pets to repair the creek banks, thus improving the health of the creek and bring the salmon back. Please help us keep up the momentum. We are working on increasing signage to make people aware of designated trails, as this is part of the problem.

What Can be Done At Home

Everyone can do a little. You may not realize it but even things you do at your home can impact a creek near you. Anything you wash off your car, using windshield washer fluid, soaps, pesticides and so forth will eventually wash into the storm drain. Some things are unavoidable but just being mindful can minimize the impact. If you can, increase the porous surfaces on your property, perhaps use a downspout disconnect, as pictured below, so that some of the water runoff can be filtered by the earth.

The PKOLS-Mount Douglas Conservancy has partnered with some great organizations to release chum fry into the creek in hopes they will imprint and return to spawn as adults. In addition to this, there are also salmon carcasses tossed into the creek annually to mimic the natural lifecycle. This provides nutrients to the ecosystem, therefore improving the health of the creek. There has been extensive work done to repair the creek banks and replace plant life to prevent further erosion. Salmon spawning gravel has also been hauled in, along with large rocks and tree root balls being strategically placed in the creek to minimize the impact of storm surges.

Pacific Salmon Foundation

The Pacific Salmon Foundation (PSF) has been a key partner in the successful restoration of Douglas Creek for spawning Coho and Chum salmon. Douglas Creek has been one of 16 projects supported by the PSF in Victoria, that is helping to return the salmon to our local waterways through a grant that was released in 2020. They have been an invaluable partner in helping our society restore the creek, with grants over the years.

Douglas Creek Watershed

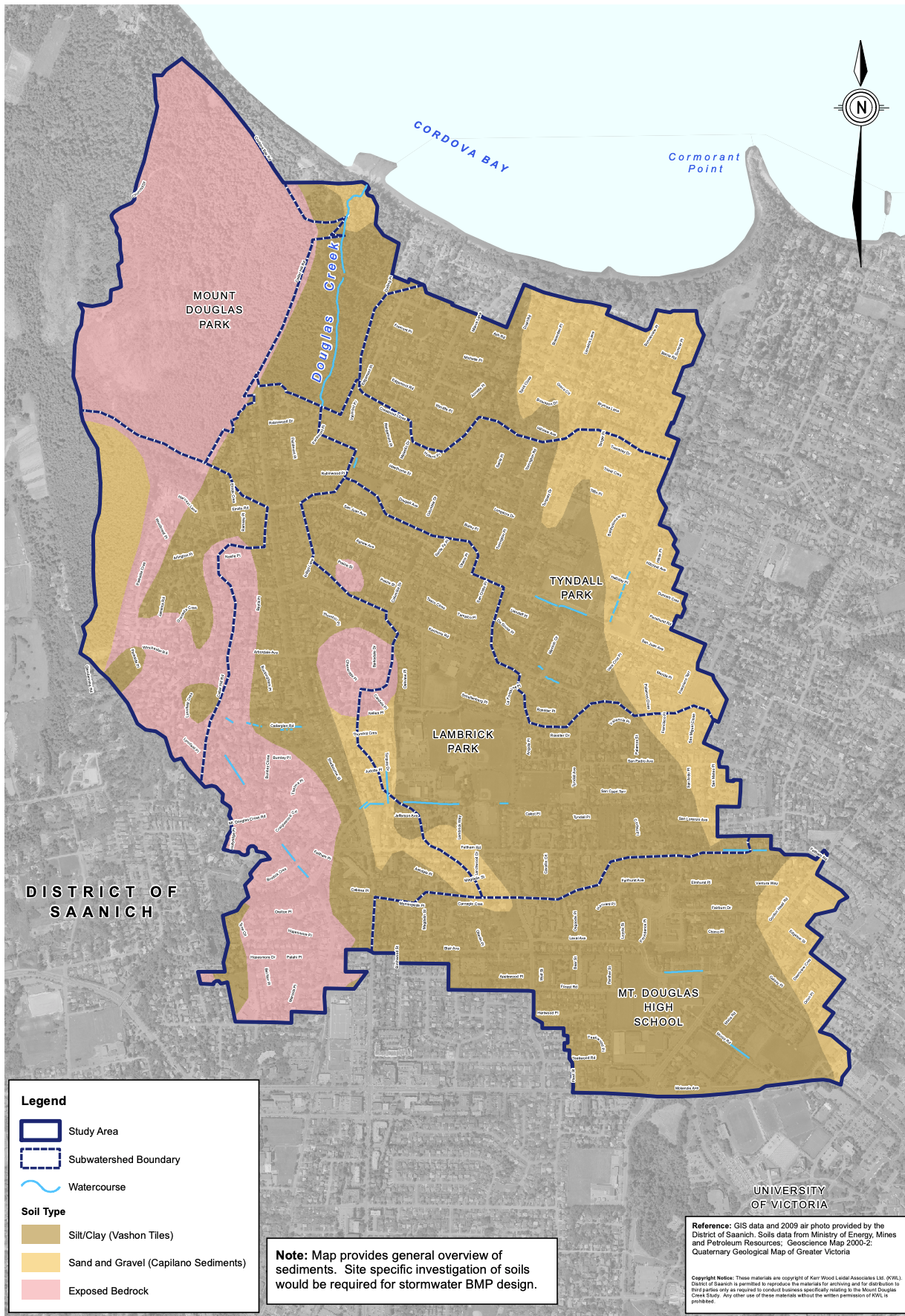

The Douglas Creek watershed covers 524 hectares.

It is located in the district of Saanich on southern Vancouver Island.

One hundred and forty years of development has changed the watershed from forest to farm, to its present state of 5000 properties.

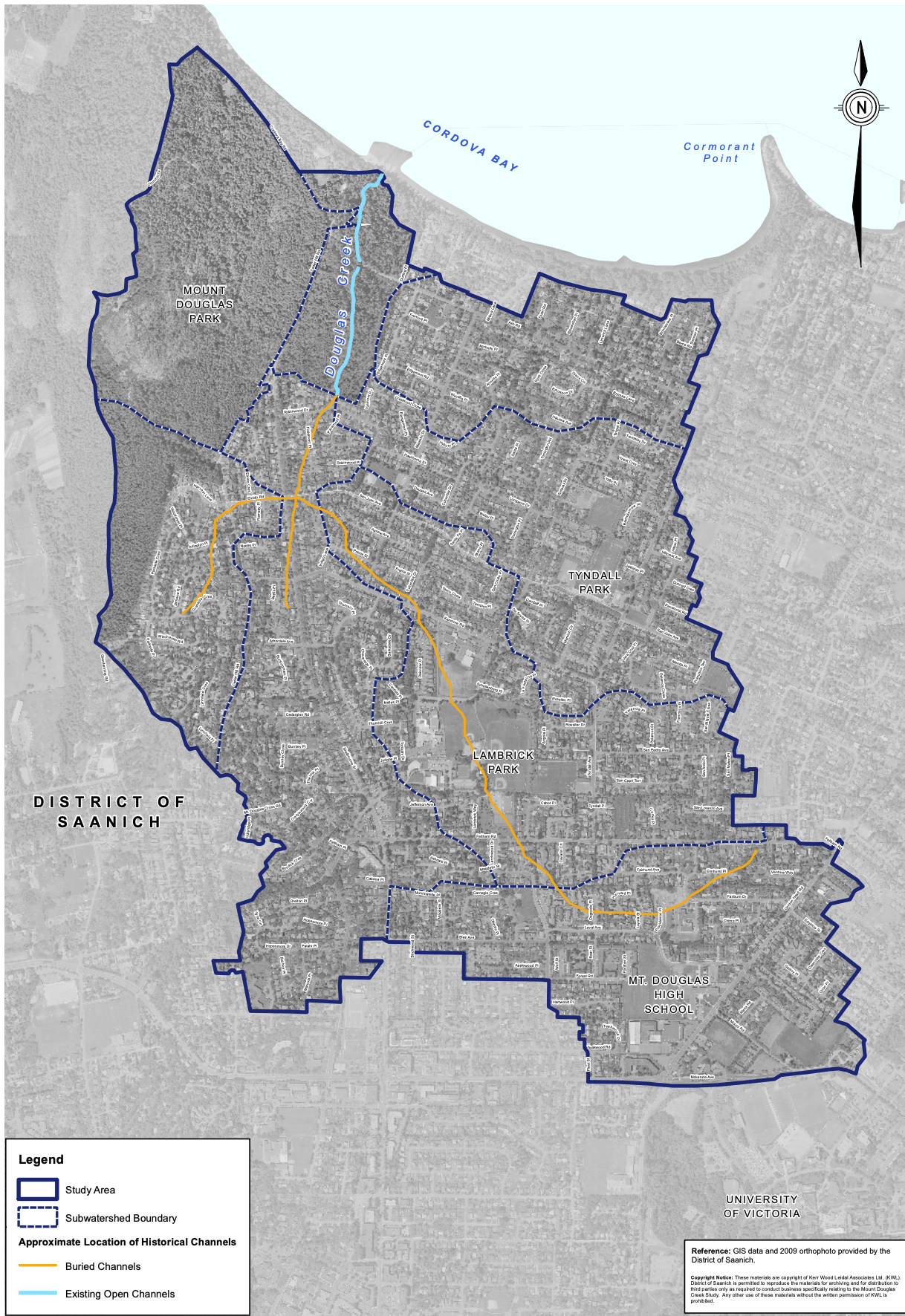

Much of the original stream channel of Douglas Creek and its upper tributaries were covered over as development progressed.

About 1.1 km of the lower stream remains. It flows south to north through the easterly portion of Mount Douglas Park.

The riparian ecosystem along the stream is largely intact and is a fair example of the biodiversity of coastal Douglas Fir forests.

However, the developed portion of the watershed is having an ongoing impact on stream habitat.

The problems are typical of urbanized watersheds everywhere – erratic water quantity due to a high percentage of impervious area, degraded water quality, and diminished aquatic ecosystem biodiversity. The stream channel shows all the effects of seasonal flood water – eroded stream banks, a channel that is deeply incised into a clay substrate, gravel loss, and a lack of large woody debris. Pollutants enter the stream as chemicals from automobiles, lawns and driveways. Continued urbanization is having an impact on this locally important stream.